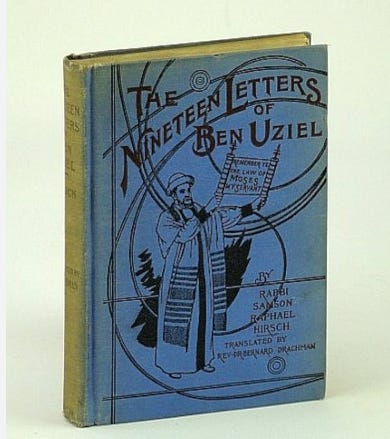

The sefer that most clearly impacted my thinking as a ben Torah is Rav Samson Rephael Hirsch’s Nineteen Letters of Ben Uziel. Looking back, I think what made the strongest impression is the fact that the sefer intends to present a comprehensive framework of Judaism — the forest, rather than individual trees.

Until then, much of my Jewish education and my own learning focused on individual details or topics. Even hashkafic discussions tended to analyze an individual topic and present a number of different approaches before moving on to the next topic. What Rav Hirsch does in the Nineteen Letters is systematically develop his understanding of day-to-day avodas Hashem as rooted in the fundamental goal of Torah and mitzvos writ large. This way, he succeeds at building an outline that he later filled in with Horeb, his monumental Commentary to the Torah, a Commentary to the Siddur, Commentary to Tehillim, and nine volumes of Collected Writings. This was a lightbulb moment for me; it was the equivalent of spending years tracing arbitrary marks on a page and then finding out that those marks were actually letters that could be combined to create words and convey meaning.

My goal is to take a letter or two at a time and try to add additional context to the outlines Rav Hirsch provided in the letters as well as examples to help illustrate some of his ideas. In this way, I hope to bring his words to more people. As he himself wrote:

Having scaled a summit by myself and gained new vistas, I would like to summon companions; I would like to descend and, together with them, retrace the road from the beginning. I want to give over only what I have been able to gather so far, not as a finished work, but truly as mere “essays.”1

Read along here. Next week, Letter 1: Benjamin’s Questions. As you read, consider if Benjamin’s questions feel like they were written in 1836 or in 2025.

Background of the Sefer

The origin of the Nineteen Letters is itself a story. Rav Hirsch was a young rabbi in the town of Oldenburg in the early 1800s. The Enlightenment was in full swing and shaking the foundations of observant Jewry in Europe. (To give a sense of what was happening, the president of Rav Hirsch’s community in Frankfurt shared that when he was a teenager, he was the only one of all his friends who was pointing on tefillin every day.2) Realizing that the teachers in his town needed reliable and relatable texts to teach from (Rav Hirsch’s emphasis on investing in education was a consistent theme throughout his life3), he authored a massive volume exploring the reasons for many of the mitzvos. Titled Horeb, one name for Har Sinai, where the mitzvos were given to Moshe Rabbeinu, he planned to write a second volume, Moriah, exploring the “essence of Jewish nationhood,”4 the ideological underpinnings of Judaism.

When Rav Hirsch approached a number of Jewish publishers with the manuscript of Horeb, they turned him down. They didn’t see much reason to invest in publishing a sefer defending what they thought was a religion on its last legs. Undeterred, Rav Hirsch turned to a non-Jewish publisher, who had a different concern: Because Rav Hirsch was so young (he was only 28 at the time) and had never published before, how was he to know that anyone would be interested in what he had to say? To address this concern, Rav Hirsch wrote a summary of the basic ideas of both volumes, Moriah and Horeb — The Nineteen Letters of Ben Uziel. The Jewish world owes a significant debt of gratitude to this non-Jewish publisher, as for some reason, Rav Hirsch never ended up writing Moriah. Our only record of what he would have written is contained in Letters 3–9 of The Nineteen Letters.

Reception of The Nineteen Letters

The Nineteen Letters was met with an enthusiastic reception. Defenders of Orthodox Judaism were breathtaken by modern formulations of traditional ideas that cogently addressed the questions of the time. Its sophisticated presentation — Rav Hirsch wrote in an impressive High German — increased its appeal especially to young Jews. Although close to two hundred years have passed since the sefer was published, it still manages to feel overwhelmingly relevant to our times — the mark of a true classic.

Structure of the Sefer

The Nineteen Letters was written as an imagined dialogue, like the Kuzari. In this case, the conversation is between two friends, Benjamin and Naftali. The sefer can be broken up into three main sections, along with an introduction and conclusion.

Letter 1 introduces the book with a number of questions from Binyamin, a now-secular Jew, to his old friend Naftali, now a young rabbi (this is the only time we hear from Benjamin in the book).

Letter 2 conveys Naftali’s invitation to return to the fundamentals of Judaism in order to respond to Benjamin’s questions.

Letters 3–9, summarizing Moriah, explain the progression of the Torah from Gan Eden to Galus, expounding on the purpose of humanity, the message of history, the role of the Jewish People, and the function of the land of Israel.

Letters 10–14, summarizing Horeb, highlight in brief how different mitzvos convey messages meant to be internalized and practiced.

Finally, Letter 15 returns to Binyamin’s questions from Letter 1 and shows how the framework built over the previous letters answers them.

Letters 16–18 contain Rav Hirsch’s thoughts on issues like Jewish involvement in non-Jewish society, the impulse to reform Judaism, and the proper approach to talmud Torah.

Letter 19 concludes by foreshadowing the publication of Horeb, as well as a goosebump-inducing reflection on why Rav Hirsch chose to publish The Nineteen Letters.

Rav Hirsch’s Vision

To give a taste of Rav Hirsch’s writing, consider this vision that Rav Hirsch described as motivating him to begin writing Horeb:5

I saw Peretz [an imaginary Reformer] at the head of a crowd, seized like him by wild frenzy, storming on to the Lord's House, waving their burning torches. Calm and exalted stood the Temple of the Divine Law on the top of the mountain. The mountain itself was crowded from top to bottom with the endless rows of all the noble men who in times gone by, for more than three thousand years, had lived and died for the Divine Law, teaching and heeding, doing and fulfilling the words of instruction of God's Law, protecting it and fighting for it till the last breath. They saw the frantic crowd, heard their yelling shouts of joy. They recognized the aim of this wild onslaught and sadly bowed their heads and covered their faces. They were used to blows from strangers, from the enemies of their God, their people and their law. They were willing to die and conquer for their people and its spiritual heritage, but not to offer the blushing cheek to the blows of their own sons. They covered their heads in shame; but the crowd stormed on, waving their torches. Mockingly they singed the heads and robes of the Jewish Sages, flung the ancient books upon the stake. The crackling flames devoured them and the sparks blew heavenwards.6

The Holy Temple still stood erect in serene calm and the crowd would have liked to spare it; but the flames kindled by them had gone beyond their control. A billowing wave of fire covered the Temple mount; the heat of the fire forced open the gates of the Sanctuary and in moved the flames which Israel's own sons had kindled. The Sanctuary burned down, together with the Altar, the Holy Table and the Curtain. The flames penetrated the Holy of Holies and devoured the Tablets of the Law. From the Mountain of Zion, the wild-fire spread through countries and towns, burning to ashes all that was sublime and holy until the world was a smoking wilderness; until, finally, the fire had spent itself on a world-wide and desolate scene of conflagration.

Thus the destructive torch kindled by frantic hands, having first been turned against tradition, destroyed God's Sanctuary in the end, together with all that was noble and holy in man; and finally it devoured the torch-bearers themselves. As I gazed into the gruesome night, I saw the last flicker of Peretz's torch going up in smoke.

This sad vision, however, was soon followed by another one of sublime beauty:

It was dawn; the beams of the rising sun shone upon a long row of imposing men, clad in shining white robes. They were Israel's Elders, Judges, Prophets, and the Men of the Great Synod, the Sages of the Talmud and the great Rabbis of succeeding generations. Leading this elevated assembly was Moses our Teacher. His face radiated with heavenly splendor. The light that broke forth from Moses's countenance lit the Candelabrum, which had miraculously remained intact when the Sanctuary burnt down. And as the glowing light surrounded the Candelabrum, behold, the Temple rose again in its serene calm. Altar and Table reappeared and the Holy Curtain covered once more the Holy of Holies. The Divine Law rested again in the Ark, protected by the Cherubim, of the Lord. The earth was again filled with joy and blessing. And behold, Moses our Teacher approached me and said: "How could you hesitate, my son, as you saw the struggle of delusion against truth, of man against God! Human arrogance and lack of insight had removed Heaven from the Earth, had called my work that which was in reality the work of God, and had described the loyal Messengers of the Divine word deceivers and impostors. And you could hesitate inactively even for a moment!"

And with this in mind, Rav Hirsch began writing Horeb.

Read along with us here. Next week, Letter 1: Benjamin’s Questions. As you read, consider if Benjamin’s questions feel like they were written in 1836 or in 2025.

Letter 19.

Similarly, he dedicated Horeb to “the thinking young men and women of Israel,” and the first thing he did when he came to Frankfurt was go door to door recruiting students for the school he opened.

Letter from Rav Hirsch to a friend, printed in the beginning of Horeb, Soncino ed.

Introduction to Horeb, xxviii–xxx.

Similar imagery returns in Letter 19.