After surveying the messages conveyed by the Torah and mitzvos, “Naftali” circles back to Benjamin’s questions from Letter 1. He addresses each point using our newfound perspective:

“Judaism doesn’t bring a person to his true purpose, which is happiness and perfection.”

Naftali’s response:

“Judaism does not accept your conception of man’s purpose and, indeed, strenuously opposes the pleasure-seeking and the worship of material possessions that it entails.” Hashem created a world as a complex web of giving and taking, a Circle of Life, and mankind is meant to proactively choose to participate in that process. The purpose of life is to use everything we have/are given as means to the higher end of Divine service.

“The Jewish nation has suffered for thousands of years (the opposite of achieving happiness.”

The suffering we have experienced is a result of our failings as a nation (see Letter 9, Exile). And still, even while suffering in exile, we were still given the opportunity to live up to our purpose in representing Hashem to the broader world, sometimes even better than we managed to so with our own country.

“The Torah interferes with all the joys of life and denies every pleasure.”

In fact, the Torah ennobles natural pleasures and directs inborn drives toward hallowed purposes. In the proper context — as means to an end rather than ends unto themselves — these drives and pleasures are “holy and truly human, a way of fulfilling the human destiny.” As expressed by the laws of Nazir, the Torah considers “arbitrary, purposeless abstinence from permitted pleasures a sin.”

“The highest degree of Divine service… is ‘joy before the Lord,’ serene joyfulness in life, flowing from our awareness that our life, our thinking, our feelings, our speech, our actions, our joys and our sorrows are all the object of God’s attention.”

“The Jewish People have not made any contribution to the edifice of human civilization.”

What about the idea that generates meaning for everything that all the other nations have created — that mankind has a role to play in the world as senior members of the Divine orchestra? Pretty important contribution.

“The Torah isolates the Jewish People.”

Very true — how else do you expect us to maintain a separate set of values until everyone else gets on board? At the same time, this is not meant to yield “enmity or pride.” After all, the job of the Jewish People is to make Hashem known as the One who calls all human beings to His service (chaviv adam she’nivra b’tzelem). “Does not Yisrael consider universal acceptance of the brotherhood of mankind to be its ultimate goal” Do we not implore God, on almost every page of our prayers, to further this goal? We are all working on one great edifice…”

“The spirit of the Jew is crushed by the submissiveness demanded of it by the Torah.”

Rav Hirsch’s answer is that we actually demonstrate supreme strength of character. While he gives his own example, what comes to mind for me is the mindboggling turnaround of walking out of the concentration camps in 1945 and establishing a state in 48.

“The Torah inhibits creativity and art.”

Generally not true; the only limitations are related to avodah zarah, “for Judaism rates truth higher than artistic expression.”

“The Torah’s dogmas bars the way to free thought and speculation.”

Unclear what he even meant by this, but Rav Hirsch has a great response. By accepting Hashem as the Creator of the world, we ratify the importance of learning more about His world — in the context of service. “Our conclusions about the nature of all things must be derived from observation, from experience and from the Torah… True speculation takes nature, man and history as facts, investigating them in order to arrive at knowledge. To these, Judaism adds the Torah.”

Rav Hirsch also adds some comments about the true/ideal approach to learning, but we’ll save that for Letter 18.

In response to Benjamin’s description of a young rav who spends his days cloistered in the corner of the beis midrash, Rav Hirsch actually affirms that the ideal Jew is one who is involved in the world and invested in the well-being of others. “A chassid is a person who totally gives himself in love… lives only for others, through acts of lovingkindness… A life of seclusion, of only meditation and prayer, is not Judaism. Torah and avodah (study and worship) are but pathways meant to lead to deeds.”

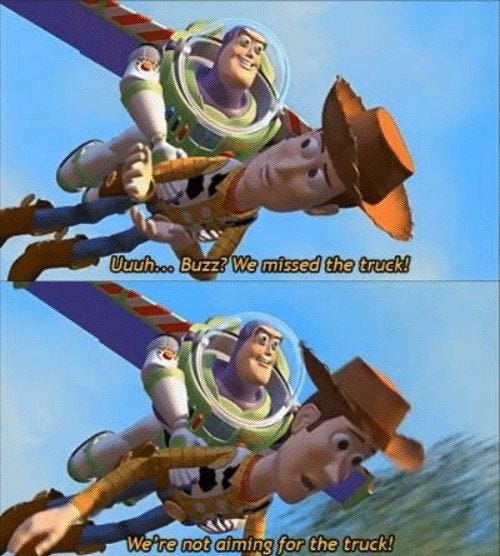

“What about the difficulties caused by the observance of the Torah, and the limitations it imposes upon our traveling, dealings with gentiles, and business activities?”

This is one of Rav Hirsch’s most powerful responses, and it is worth reading in full inside (pg. 202–204 in the Feldheim Elias ed.). In brief, Rav Hirsch says two points. First, halachah should be recognized as valuable enough to justify any sacrifices it has us make, the same way people are willing to sacrifice for anything else they value in life. Second, claims of sacrifice more likely betray a perspective that is focused on amassing possessions/wealth as the goal of life rather than a means to a life of Divine service, and an attitude that says I am responsible for my own financial success rather than recognizing Hashem as bringing about the results a person sees.

“But what about our relationships with gentiles? We make ourselves so conspicuous, we are recognized at once as Jews.”

Who told you to hide your Jewishness?! “Be a Jew, a true Jew; strive for the ideal of the real Jew, the fulfillment of the Torah in justice and lovingkindness. Seeks to command respect because of your Jewishness, not in spite of it.

Reminds me of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ oft-repeated line:

Yes, there are halachos that restrict a Jew’s ability to form close friendships with gentiles, and certainly to marry and join their family. As above, these are necessary to maintain the integrity of Torah and Jewish values; our goal is to lead the rest of the world up to Hashem, not forfeit the gift we’ve been given to live an uninspired life.

Still, living as a true Jew will earn their respect — “Practice righteousness and lovingkindness, as the Torah teaches you; feed their hungry, clothe their naked, comfort their suffering, heal their sick, counsel the misguided, assist them by word and deed. In short, display the entire noble breadth of your Judaism. Do you really think that they will not respect and admire you…”

“Once you comprehend your aim in life and Yisrael’s calling, all your complaints about the difficulties of upholding Judaism will vanish.”

Diving Deeper

Value of Hashkafah

This entire letter is a perfect example of the value of a well-developed hashkafah. Benjamin had a laundry list of questions about the Torah and Jewish life. The ideas developed over Letters 2–14 allowed Naftali to respond to each point. And even more than that, the responses are cohesive and work together, rather than responding to each question on its own with a collection of unrelated sources.

Interesting Pasuk Translation

Rav Hirsch opens this letter with a unique translation of a pasuk to express Benjamin’s newfound perspective on Judaism.

“So you have taken as your motto the verse quoted in my previous letter:

‘O that Thy servant, too, might be illumined by them!

If he keeps them, how great the path of life!’”

This is Rav Hirsch’s translation of Tehillim 19:12:

גַּם־עַבְדְּךָ נִזְהָר בָּהֶם בְּשׇׁמְרָם עֵקֶב רָב

He’s translating nizhar not as “treat them carefully,” as it is normally translated, but as “shine,” like in the phrase “k’zohar ha’rakia mazhirim.” Likewise, rather than translating eikev as “reward,” as the Metzudos Tzion does, he reads it as “path,” presumably related to eikev meaning “heel.” Accordingly, this pasuk expresses the attitude towards mitzvos Rav Hirsch described over the last few letters: sources of illumination that provide guidance in properly navigating life. Rav Hirsch reads many pesukim in Tehillim as expressing this perspective, especially in perek 119.

“Come to See Me”

Rav Hirsch has Naftali invite Benjamin to come visit him to learn about the ideas expressed more deeply than is allowed in a written format. An interesting historical note is that Rav Hirsch himself actually hosted someone in his home for two to three years — the noted historian Heinrich Graetz (born “Tzvi Hirsch”). As a young man, he was profoundly influenced by the Nineteen Letters. Once it became known that Rav Hirsch was the author, Graetz wrote to him, requesting to stay with him in his home, and Rav Hirsch accepted. (I think there is a record of the schedule Rav Hirsch followed during that period in Graetz’s diary, but I didn’t find anything online.)

While Graetz was inspired by this experience, he eventually parted ideological ways with Rav Hirsch. When Graetz published a well-received set of books on the History of the Jews that included a number of claims about Torah She’baal Peh, Rav Hirsch responded by highlighting the inaccuracies in his claims and by showing how he left out parts of sources that contradicted his thesis.

More to talk about in this packed letter, but we’ll call it here,

Next week, Letter 16 — Emancipation.