While I’ve taught the 19 Letters a number of times, I have not yet hit upon a way to present these letters in a way that feels personally satisfying. Rav Hirsch summarizes in single lines ideas that he takes pages to develop in Horeb; how am I supposed to do that justice here?

Toros

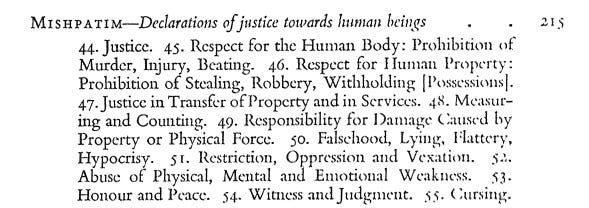

Let’s start with a survey of the mitzvos Rav Hirsch includes in each category. While you won’t get that from this letter, a peek at Horeb will give it to you:

With his opening lines, Rav Hirsch stresses that these are less commandments of belief (he states elsewhere that Judaism has no “dogmas of faith), but “truths revealed by history” that should be accepted as “principles that govern our lives.” For example, the second mitzvah on the list, Unity of God, is often taken as a philosophical truth — a person must believe that Hashem is one, but in a way that has no physical analog (see first perek of Rambam’s Yesodei HaTorah). Rav Hirsch, though, stresses the practical takeaway from this reality:

That He is One, which challenges you to give thought to every aspect of your life and to unite all of your faculties, means and circumstances in the service and for the purposes of the One from Whom they all derive.

Similarly, in Horeb:

Just as the world, with all its variety, history with all its change, has its origin in the one source, is guided by one hand, serves One Being and strives upwards towards this One; so must you recognize and feel your life with all its changes to issue from one source, to be guided by one hand, to flow towards one goal. You must comprehend your life with all its diversity as proceeding from this One and you must direct it towards this One, in order that your life may be a unity just as your God is One. With mind and body, with thought and feeling, with word, deed and enjoyment, in wealth and poverty, in joy and sorrow, in health and sickness, in freedom and slavery, in life and death, your life-task is everywhere and always the same for it all proceeds from One God and has been assigned by the One God as your task in life; therefore everything is of equal significance, for in everything and with everything you have been summoned to the service of the One God. Strive to reach this One, and be one in heart as your God is One.

Of course, Rav Hirsch sources this in the opening line of Shema. For Rav Hirsch, this twice-daily recitation is not meant to be an anti-idolatry screed, but a reminder to dedicate all of one’s self to Hashem and one’s mission in life.

Rav Hirsch also includes some ideas that aren’t classically described as mitzvos. For example, third in this letter:

That all His creatures are His servants, and you, too, must join their ranks to labor in His service.

In Horeb, Rav Hirsch titles this the mitzvah of “Self-Appraisal” — not one you hear about too often:

Young men and young women of Israel! Let the consciousness of your mission penetrate you through and through! Be ever conscious that the same God Who has prescribed the course of the sun, the path of the light-ray, the development of the worm, has in His Torah also given to you the law of your life. And, with this consciousness, live in God's creation, as brothers and sisters of the greatest as of the smallest, all like you, you like all, called upon to be servants of the One and Only. Rejoice in this company! Then will the rolling thunder, the effulgent sun, the blade of grass that nods to you as you walk, the breeze that fans you as it passes, greet you and remind you of your task, which, like theirs, is to serve your God and not to fall out of their company. For, indeed, if, alas, you misuse the gift of your freedom in order to withdraw yourself from the service of the One God, then you sink not only below the beneficent orb of the sun but beneath the worm on which you tread and the stone which, faithful to its duty, patiently sustains your weight.

(I’m resisting the urge to just copy-paste the entire piece here.)

These two mitzvos should call to mind Letters 3 and 4 — which is exactly the point. Rav Hirsch’s entire approach is that the ideas he discussed in Moriah — Letters 3–9 either flow from or are expressed by the 613 mitzvos, discussed in Horeb.

Mishpatim

Let’s move on to Mishpatim — commandments of justice towards other humans.

While most of these are more easily identifiable as classic mitzvos, there are still some surprises, at least in presentation. For example, the prohibition of stealing is not a social issue, but a lack of “respect[ing] whatever is theirs as given to them by God or as having been acquired according to Divinely sanctioned law.”

In the letter, Rav Hirsch writes “Never abuse the frailty of his body, mind, or heart”; he sources this in part from Vayikra 19:16 — “Do not curse a deafmute and do not place a stumbling block in front of a blind person.” In Horeb, Rav Hirsch focuses more on the responsibility of influence — make sure that the influence you exert on others is only positive, never negative. In order to make this point, he references not only the pasuk of lifnei iver, but also the laws surrounding a meisis — someone who tries to get another to do avodah zarah. In other words, he presents a meisis as a super-lifnei iver to yield the concept of both mitzvos teaching the importance of responsible influence.

He goes on to explain what he means by each category — eye, mind, and heart, corresponding to the physical/mental/emotional of the title. Worth a read, especially for someone who works with children.

Chukim

Finally, Chukim — “Laws of righteousness (justice) towards those beings subordinate to man.”

Rav Hirsch portrays these mitzvos here as primarily commandments of respect:

“Respect for all that exists as God’s property… respect for all the species…do not intermingle them… respect for the feelings and instincts of animals… respect for the human body… respect for your own body… respect for your soul, when you nourish its tool, the body… respect for your own person in its purest expression — your power of speech.”

While each mitzvah is worth exploring, what’s most significant here is the very fact that Rav Hirsch is attempting to offer reasons for these mitzvos at all. Chukim are often portrayed as the “black boxes” of mitzvos. Even those who believe that mitzvos generally have reasons that we are meant to understand sometimes throw up their hands when they come to chukim — but not Rav Hirsch. It is important to reiterate that we are committed to doing the mitzvos whether understand them or not, but the ultimate goal is understanding. See Rav Hirsch’s Foreword to Horeb (pg. clv), where he explores both sides of the above in depth.

Diving Deeper

Only one this week.

Rav Hirsch dedicated Horeb to the “thinking young men and women” of the Jewish People:

If you can’t read German (like me), here’s ChatGPT:

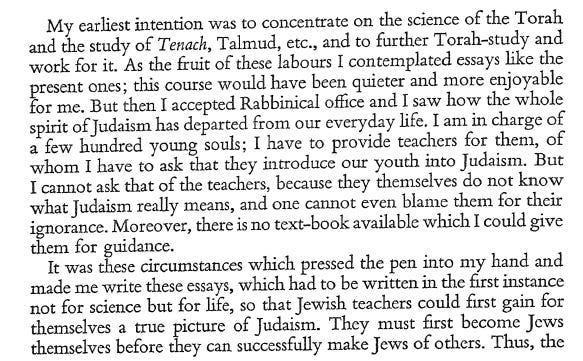

This is a consistent theme in Rav Hirsch’s writing as well as practical approach to leading his communities. As he writes to his friend Z. Mays (in a letter included in the introduction to Horeb), the reason he began writing Horeb and eventually the 19 Letters in the first place was in order to provide some sort of textbook for the teachers in the community he was responsible for as rabbi.

Throughout Horeb, including in the second excerpt cited above, Rav Hirsch speaks directly to his intended audience, “Young men and women of Israel!”

So convinced was he of the importance of building up the youth that one of the first things, if not the first thing, he did upon arriving in Frankfurt, the once-great Jewish city that had been decimated by Reform, was to go door to door recruiting for students to join the Jewish school he planned to start. Somehow, he was wildly successful, starting with around 80 students (and, if I understand correctly, essentially inventing the yeshiva day school model that combines limudei kodesh and limudei chol, which has become the standard across much of the Jewish world. But I may be wrong about that).

It is not a coincidence that an entire volume of his collected writings is dedicated to chinuch. In the first essay, he calls education “the most sacred of causes,” wondering (paraphrased) “What have we accomplished by investing in the older generation if the education of the younger generation is left to chance?”

My personal experience has been that Rav Hirsch’s writings continue to resonate with “the thinking young men and women of Israel,” including a wide range of backgrounds and exposure to learning.